While the concept of “lions and tigers and bears” may prompt some to say, “Oh my!”, for Case Western Reserve doctoral students Maura Plocek and Kaylin Tennant, they’re part of their daily routines.

As PhD candidates in biology at the university, the pair are taking advantage of CWRU’s partnership with Cleveland Metroparks Zoo—the only of its kind in the country—which provides them with graduate student support and access to zoo staff as primary advisors.

The partnership is a part of the BioScience Alliance, a high-impact collaboration of Cleveland-area research and training programs which also includes the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and Holden Arboretum. The alliance creates unique internships for undergraduates and opportunities for graduate students to partner with these institutions to conduct research for their dissertations—just as Plocek and Tennant are doing.

“Under the supervision of staff scientists at Cleveland Metroparks Zoo, our students gain an understanding of challenges facing wildlife populations in human care,” explained Kristen Lukas, director of conservation and science at the zoo and adjunct assistant professor at CWRU, who was instrumental in establishing the partnership. “[They then] craft meaningful research questions that have a direct—and often immediate—impact on animal care and welfare.”

Monkey business

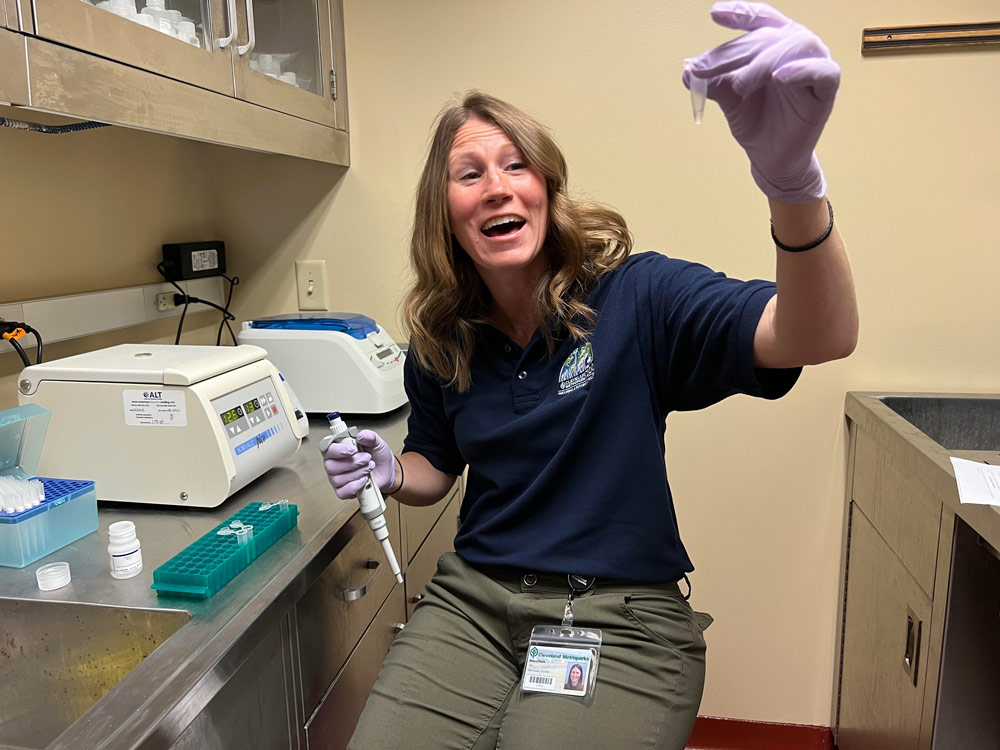

For Maura Plocek, no two days in this program look the same. Some are spent entirely in the lab while others involve observing animal behavior—something a 7-year-old Plocek could only have dreamed about.

The Pittsburgh native can trace her passion for animals back to a visit to the Atlantic coast of Maine, where she had a close encounter with a minke whale.

“It felt like a moment right out of Free Willy—and I was hooked,” she said. “From that point forward, it has only ever been animal behavior for me.”

Today, Plocek’s passion has taken shape as research into the role of diet and microbiomes in the high rates of gastrointestinal disorders observed in zoo-housed colobines (leaf-eating monkeys).

The zoo-housed monkeys she studies have a 25% mortality rate from gastrointestinal (GI) issues and an additional 20% from the combination of other disorders with GI problems. Scientists don’t know the cause, but one of the theories is that it’s rooted in the microbes in their gut.

“What my research is really focusing on is if we can manipulate their diet—just feed them different foods in different quantities—in order to make sure that their gut health is really, really healthy,” Plocek explained, “and that it might mitigate some of those GI issues that are causing them some serious health concerns.”

Passion for primates

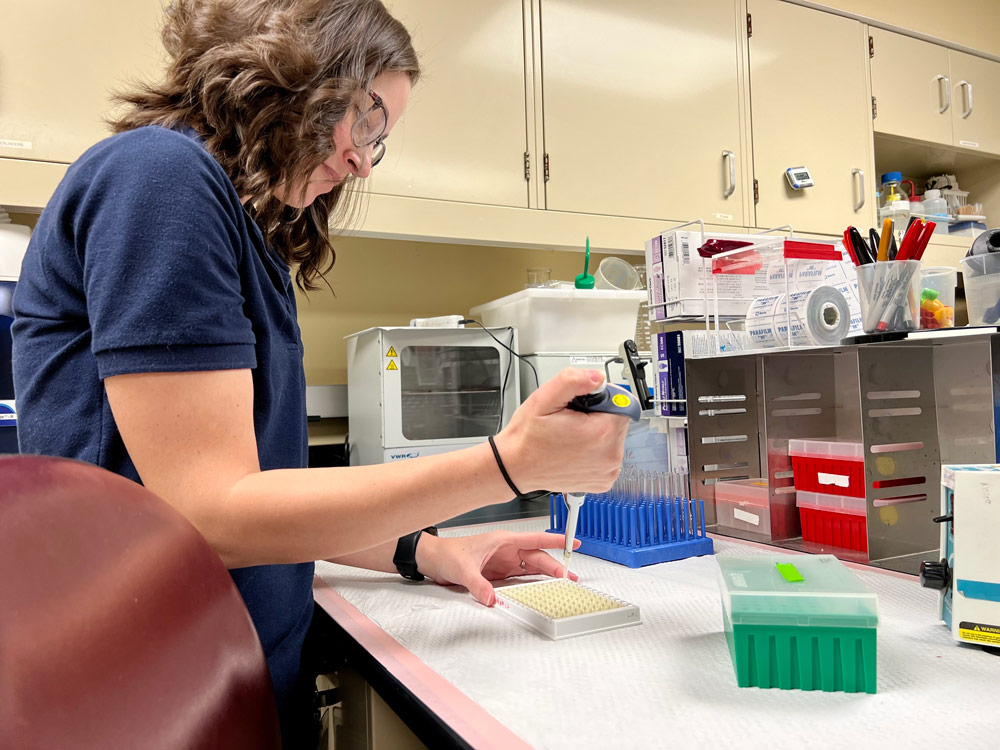

Kaylin Tennant has focused her efforts on a larger member of the primate family: gorillas. Specifically, she’s investigating the physiological mechanisms of regurgitation and reingestion in the zoo-housed primates.

Having had a love for animals as long as she can remember, Tennant went through school fully expecting to become a veterinarian, and feels her middle school self would be flabbergasted to know the career path she’s on today.

“When you’re going through elementary school, middle school, you just assume [you’re] going to be a vet,” Tennant laughed. “Like, that’s the only thing that I can do because that’s the only job out there where you can work with animals. Which is obviously not true, but that’s what I wanted to do.”

Now, she spends most of her time observing the gorilla troop, watching for instances of regurgitation and reingestion—a prevalent behavior in zoo-housed gorillas as 60% of the North American population exhibit the behavior.

“It’s never been observed in the wild, so that would indicate that something about the zoo environment is triggering this behavior,” she said. “I’m trying to figure out what that is.”

Specifically, her hypothesis deals with insulin resistance and seeing if the gorillas that participate in this behavior are insulin resistant or if they have higher levels of insulin than those who do not.

Tennant pursued her passion for great apes and biology at three universities in Indiana and Florida before she was drawn to Case Western Reserve’s program and its enticing partnership with the zoo.

“The relationship the zoo has with the university is very strong; our primary advisors are staff scientists at the zoo and adjuncts at CWRU,” Tennant noted. “There just isn’t another program like this in the country.”

Looking ahead

The Case Western Reserve and Cleveland Metroparks Zoo partnership has launched seven PhD graduates to date, all of whom have secured full-time employment in leadership positions at zoos across the country.

“These highly trained graduates—with roots here in Cleveland—are paving the way as the next generation of zoo scientists,” Lukas said.

And, some of those zoo scientists—including Plocek and Tennant—are priming the generation that will come after them. Tennant’s daughter regularly totes her bug-catching kit around with her—and she relishes the opportunity to press leaves she’s collected from her adventures around Cleveland.

Similarly, Plocek’s children show a passion for science: “My kids like to brag that ‘mom’s favorite smell is gorillas and she really likes monkey poop,’” she said with a smile. “When I come home to them and explain what I’ve done [that day]—to see that glow on their faces is very rewarding.”

Learn more about graduate biology programs at Case Western Reserve University and discover the BioScience Alliance.