Case Western Reserve University scientist PhD student applies new calculations to reveal downsizing and chunky details about species from Devonian Period

About 360 million years ago, in the shallow subtropical waters above what is now the city of Cleveland, an armor-plated fish many believed to be up to 30 feet long ruled the seas.

The species Dunkleosteus terrelli was Earth’s first vertebrate “superpredator” and lived during the Age of Fishes (Devonian Period)—when North America was near the latitude of what is now Rio de Janeiro.

But in nearly 150 years of research since fossilized remains of the prehistoric big fish were discovered on the shores of Lake Erie in 1867, scientists may have made some incorrect assumptions about Dunkleosteus’ size and shark-like shape.

In research published last month, a Case Western Reserve University scientist suggests the length of this prehistoric predator may have been greatly exaggerated—that it was much shorter and chunkier.

Cleveland mascot and Ohio’s top fossil fish

“Dunkleosteus is already a strange fish, but it turns out the old size estimates resulted in us overlooking a lot of features that made this fish even stranger, like a very tuna-like torso,” said Russell Engelman, a Case Western Reserve PhD student in biology and lead author on a study published in the journal Diversity in February. “Some colleagues have been calling it ‘Chunky Dunk’ or ‘Chunkleosteus’ after seeing my research.”

Engelman said he recognizes downsizing the iconic Dunkleosteus may not be welcome news because the big fish “is essentially Cleveland’s mascot when it comes to paleontology” (The species even had a Twitter account for a few years). As a native Clevelander, he said he originally had similar feelings.

Most research on Dunkleosteus is based on specimens in the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, which has the largest and highest quality collection of Dunkleosteus remains in the world. And its name honors both a former museum curator (David Dunkle) and a local business owner (Jay Terrell) who discovered the fossilized species.

Dunkleosteus is such a homegrown icon that in 2020, the Ohio General Assembly declared Dunkleosteus terrelli the state fossil fish.

Even so, little research has been done on the fish since the 1930s, Engelman said.

“Without reliable size estimates, not much could be said about Dunkleosteus scientifically beyond ‘look at the big, scary fish!’” Engelman said. “These length estimates were an example of something that just slipped by everyone’s notice because it was assumed this fish has been well-studied.”

Short head, short body

Most estimates of the species’ length weren’t based on hard evidence, Engelman said.

That’s because Dunkleosteus was a type of extinct fish called an arthrodire. Unlike modern fishes, arthrodires like Dunkleosteus had bony, armored heads but internal skeletons made of cartilage. This means only the heads of these animals were preserved as fossils, leaving the size and shape a mystery.

The new study proposes estimating the length based on the 24-inch-long head, minus the snout—considered a way to measure that’s consistent among groups of living fishes and smaller relatives of Dunkleosteus known from complete skeletons.

“The reasoning behind this study can be summed up in one simple observation,” Engelman said. “Short fish generally have short heads and long fish generally have long heads.”

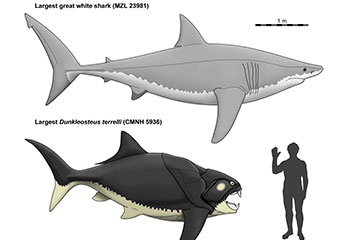

Based on that method, Engelman concluded Dunkleosteus was only 11 to 13 feet long—much shorter than any researcher had proposed before.

‘Wrecking balls’ of the deep

“Dunkleosteus has often been reconstructed assuming it had a body shape like a shark,” Engelman said.

But a shorter body and shape of the body armor also meant Dunkleosteus was likely much chunkier.

“An 11-foot Dunkleosteus is essentially the same weight as a 15-foot great white shark,” Engelman said. “These things were built like wrecking balls. The new proportions for Dunkleosteus may look goofy until you realize it has the same body shape as a tuna…and a mouth twice as large as a great white shark.”

These new size estimates also help put Dunkleosteus in a broader scientific context. Dunkleosteus is part of a larger evolutionary story, in which vertebrates went from small, unassuming bottom-dwellers to massive giants.

“Although the reduced sizes for Dunkleosteus may seem disappointing,” Engelman said, “it was still probably the biggest animal that existed on Earth up to that point in time. And these new estimates make it possible to do so many types of analyses on Dunkleosteus that it was thought would never be possible. This is the bitter pill that has to be swallowed, so that now we can get to the fun stuff.”

Patricia Princehouse, associate director of CWRU’s Institute for the Science of Origins said it was exciting to see the new work.

“This fresh take on the legendary Dunkleosteus ‘sea monster’ shows there’s still lots of brand-new breakthroughs waiting to be discovered in the world of paleontology, even with famous species,” Princehouse said. The multidisciplinary institute initiates and conducts scientific research in origins-related sciences and has promoted work undertaken by Engelman and other students.

Engelman conducted his research under advisor Darin Croft, professor of anatomy at the Case Western Reserve School of Medicine, but also advises students in biology in the College of Arts and Sciences.

For more information, contact Mike Scott at mike.scott@case.edu.