Anthony “Chip” Valleriano was 7 years old when a 3-by-4-inch, black and white photo from the early 1900s of the elaborate interior of Mother of Sorrows Catholic Church in Ashtabula first captured his fascination.

Anthony “Chip” Valleriano was 7 years old when a 3-by-4-inch, black and white photo from the early 1900s of the elaborate interior of Mother of Sorrows Catholic Church in Ashtabula first captured his fascination.

It was the church his family attended and where he would later be an altar server. But there were no colorful murals, no ornate features like those shown in the photograph. He stared at the fuzzy image wondering why his church didn’t look like the picture anymore.

It was a mystery that took Valleriano 30 years to solve. And his quest for answers also produced a book about the church’s unsung regional architect—William P. Ginther (1858-1933).

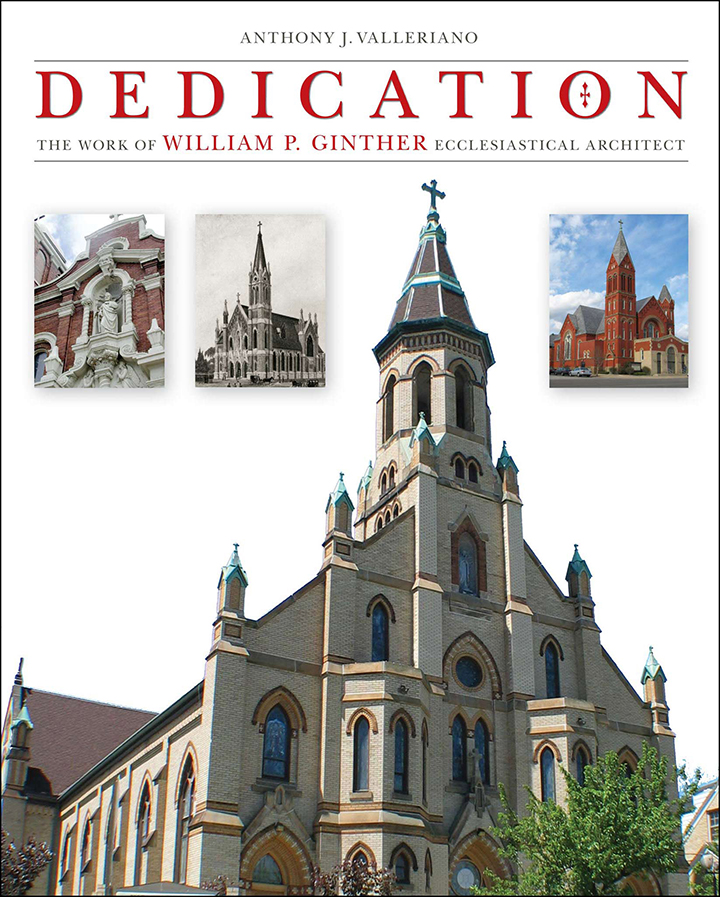

Dedication: The Work of William P. Ginther Ecclesiastical Architect (Kent State University Press; 199 pages) by Valleriano, a graphic design manager at Case Western Reserve University, is a compilation of the Akron architect’s life and legacy of more than 250 churches he designed in his career.

Valleriano’s book joins other volumes in the Sacred Landmarks Series from Kent State University and Cleveland State University that explore and preserve the history and understanding of religion in Northeast Ohio.

“Ginther impacted the lives of millions of people who worshipped in these churches,” said Valleriano. “Parishioners spent some of the most important moments of their lives in these places for baptisms, marriages, first communions and funerals. I want people to understand and appreciate their church’s history and preserve it.”

Dedication details how the son of German immigrants loved to draw at an early age and honed his skills at Buchtel College (now the University of Akron). Frank Weary, one of the leading local architects of the late 19th to early 20th centuries, became aware of Ginther’s talents and hired him to apprentice. As an apprentice, Ginther designed his first building, McKinley Church in Canton, Ohio.

Ginther eventually started his own firm and became the ecclesiastical architect for the Cleveland Catholic Diocese, designing buildings and renovations across the state. His work later expanded to major cities, from Virginia to California.

“Ginther was rumored to be the bishop of the Cleveland diocese’s favorite architect,” Valleriano said.

While an overdue acknowledgement to a man and his architecture, the book also represents the resolution of Valleriano’s personal journey for answers born of a young boy’s curiosity.

As a Mother of Sorrows Church altar server, Valleriano enjoyed a vantage point to view parts of the church not easily seen from the pews. He recalls how he would daydream during the priest’s homily, his thoughts and eyes straying to the lofty intersecting arches with ornaments that hung like stalactites in a cavern. He felt drawn to the church’s structure, but his eyes wandered back to the dome, with the question of what lay beneath the paint.

That small photo of the ornate church interior in his parent’s commemoration book reminded him how different the present church looked.

In 2002, reading about the 100th anniversary of St. Bernard’s Church in the Akron Beacon Journal, Valleriano first confirmed that Ginther built his home church from a listing of the architect’s work that accompanied the article. It prompted him to call the local historian mentioned in the article who directed him the University of Akron archives for the article.

“I felt like a detective,” said Valleriano, who cracked the mystery on who the architect was with that call. The archives faxed over an Ohio Architect Builder article from 1912 about St. Bernard’s, but, to his dismay, only text with no pictures came through. He said that fax is one of his most cherished pieces in this story.

An Internet search for the complete article led him to the library at Case Western Reserve University, where a copy of the magazine was stored on microfilm. He recalls sneaking into the library years before he came to work at CWRU in 2010. Finally, his eureka moment came.

Anticipation mounted as he scrolled through the text and illustrations appeared—including an 8-by-10-inch photograph of his church’s mural.

“I was stunned by the details in the photograph,” Valleriano said. “It is one of those moments in life where something comes full circle.”

The find again confirmed Ginther was the architect of his Ashtabula church—and the text was accompanied by that large photo with details of the mural, which depicted the Virgin Mary’s assumption.

Instead of putting the mystery to rest, the discovery only fueled Valleriano’s interest in Ginther, leading him to gather as many of Ginther’s church designs as he could find. Over the years, he searched eBay, checked out antique fairs and stores, and attended postcard shows for images of what Ginther churches looked like when first built. He even took his own photographs.

As Valleriano amassed one of the biggest collections of Ginther’s work, it prompted the idea for a book.

“I decided I should do something with it and share the information with other people,” he said. “You get an idea of how important his work was and can see the evolution of his designs over the years. Yet no one knows about him anymore, or understands or appreciates the history of his work.”

Now, he says, they can.