Case Western Reserve University researchers find impacts of 1930s lending practices persist today

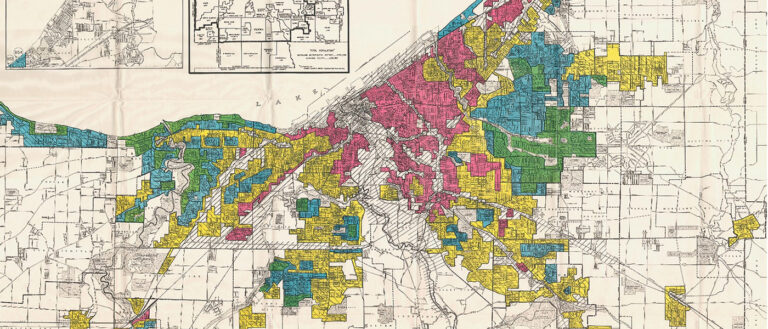

Eighty years after the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) carved up the nation’s metropolitan neighborhoods into redlined maps, researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine performed an autopsy on the discriminatory lending practice.

Specifically, researchers examined factors that went into decisions made by Ohio’s loan officers, appraisers and real-estate professionals for mortgage applications from individuals from underrepresented groups in the 1930s. The term “redlining” originates from the maps that determined investment risk; those were the areas denied home loans.

Researchers also analyzed redlining’s shameful and enduring legacy across the state.

The issue can be succinctly summarized by a passage in 1923 National Association of Real Estate Brokers textbook: “The colored people certainly have a right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness but they must recognize the economic disturbance which their presence in a white neighborhood causes and forego their desire to split off from the established district where the rest of their race lives.”

Although the federal Fair Housing Act banned the official practice more than 50 years ago, its effects continue to reverberate today.

“This study really helped us understand what determined which things were the most salient in the decision to redline a neighborhood,” said study co-author Adam Perzynski, an associate professor in the departments of medicine and sociology also affiliated with the university’s Schubert Center for Child Studies. “One of the reasons we felt this was important is that we had a hunch that these were racially discriminatory decisions, and we wanted to rule out other reasons.”

He said other factors—such as housing condition and vacancy rates—went into the determination, but “racial discrimination was the overriding factor in decisions to redline neighborhoods.”

Neighborhoods in Ohio with any Black families in the 1930s were 40 times more likely to be redlined, according to the research.

The team’s findings were published in the Du Bois Review, a peer-reviewed academic journal covering multidisciplinary and multicultural social science research and criticism about race.

“We know retrospectively that the reason neighborhoods were redlined is because African American families lived there, but we wanted to closely examine the tools that were used in the decision-making in the 1930s,” said Kristen Berg, the study’s co-author and an assistant professor at the School of Medicine, who previously worked on research into redlining while a research associate at the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences. “These are neighborhoods that still have high minoritized population with the highest rates of vacancy in their respective metropolitan areas.”

Ohio’s role in redlining

Existing research has examined individual cities across the United States using a single data set—for example, from neighborhoods, cities and regions—but this new work highlights the data from across the state, except Columbus and Cincinnati. Data from those cities once existed but has never been recovered.

Researchers studied archival maps and area description forms from the HOLC, produced between 1934 and 1940 for 568 Ohio neighborhoods. They pulled both redlined maps and questionnaires from several sources, including the National Archives.

While the formal practice of redlining is uncommon—outlawed in 1968 by the Fair Housing Act—its legacy continues, researchers found. Ongoing consequences include poverty and life-expectancy, a reason why medical school researchers got interested in the research in the first place.

“When we look at redlining, we have to think about the consequences of racist policies,” Perzynski said. “Community gardens are a good thing and managing blood pressure is never a bad idea, but they don’t correct 100 years of discrimination and institutionalized racism.”

Researchers are hopeful their findings can influence social and health policy efforts to invest in communities.

“We’ve created these neighborhoods,” Berg said. “These are the consequences of deeply intentional policy decisions. There needs to be intentional work, then, to transform neighborhoods and invest in families whose generations have been harmed by redlining.”

Perzynski and Berg were joined in the research by Douglas Gunzler, associate professor; Charles Thomas, research biostatistician; and Ashwini Sehgal, the Duncan Neuhauser Professor of Community Health Improvement, all from the School of Medicine; and researchers at The MetroHealth System in a partnership with the university.

For more information, contact Colin McEwen at colin.mcewen@case.edu.