By the time she was 6, Rebecca Barchas knew she wanted to be a doctor—and not just any kind of doctor: a psychiatrist.

Credit her mother, who was reading her adult classics like The Microbe Hunters, along with tales of women in science and medicine.

“She opened my eyes to the fascinating workings of the human mind,” Barchas recalled, “and I conceptualized that the way to combine all of these things was to become a psychiatrist.”

After graduating from Case Western Reserve University’s medical school in 1975 and completing her psychiatry residency at University Hospitals of Cleveland in 1979, she went on to realize that dream.

And this year she achieved another: establishing at Case Western Reserve an endowed professorship in translational psychiatry, with additional resources to support that faculty member’s research.

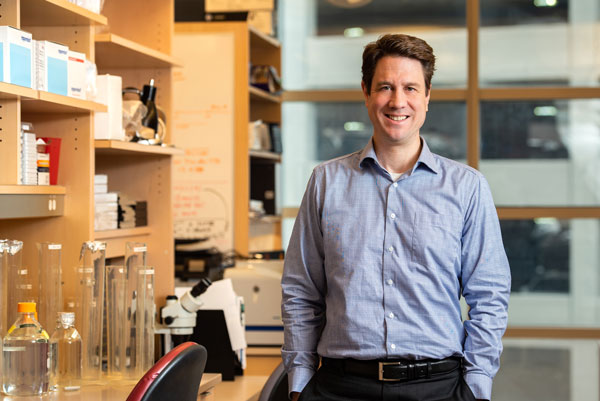

Last week, the medical school celebrated the inaugural recipient of the Barchas chair, Case Western Reserve University Psychiatry Professor Andrew A. Pieper, an accomplished psychiatrist and neuroscientist dedicated to both treating patients in his outpatient clinic and discovering treatments in his laboratory that alleviate or even cure the damage of brain trauma and neurodegenerative diseases.

“This is exactly what I’ve wanted,” Barchas said. “This is what I’ve wanted for 40 years—ever since I first had the image. This is the type of person I wanted in this chair.”

Translational psychiatry, an area of passion for Barchas since childhood, involves the process of first making basic science discoveries in laboratory models—think test tubes, cells or mice—and then advancing those findings to the development of new medicines for patients.

“Dr. Barchas’ extraordinary gift to the School of Medicine continues her family’s legacy of supporting the advancement of discovery and scholarship,” medical school dean Stan Gerson said of her $3.5 million commitment. “We are deeply grateful to her for this remarkable gift—establishing the Rebecca E. Barchas, MD Professorship of Translational Psychiatry—which bridges scientific research with the prevention, treatment, or cure of psychiatric and neuropsychiatric illness.”

Barchas’ gift, and her career path, reflect the lessons she learned from transformative figures who influenced and shaped her throughout her life—from her parents, oldest brother and other siblings, to her husband and medical school and psychiatry residency mentors.

A psychiatrist and neuroscience researcher, her brother Jack welcomed her to his Stanford University laboratory during her summer breaks from college. The experiences inspired deep admiration for him and other researchers whose work provided tools and medications that clinical psychiatrists could use to help patients. It also helped prepare her for medical school.

Arriving on CWRU’s campus for her medical school interview, Barchas met Jack Caughey, dean of student affairs and professor of medicine. When the conversation concluded, she asked when she might learn whether she was accepted.

“He said: ‘You know right now. You’re in!’” Barchas recalled. “I jumped to my feet and gave him a hug—surprising us both.”

It was at Case Western Reserve that she met the man who would become her husband, the late John A. Gehrs (LYS ‘68; GRS ‘69, American studies; GRS ‘75, philosophy). She also met Douglas Bond, former dean of the medical school, who had a profound effect on her training and sense of connection to CWRU as the place she would ultimately want to endow a professorship.

But it was the words of Caughey, when Barchas returned for a campus visit in the 1980s and shared with him her early interest in creating a chair, that stuck with her: “Endowed chairs are what make good medical schools become great medical schools.”

For Pieper, who is also director of the Center for Brain Health Medicines at University Hospitals Harrington Discovery Institute and director of the Translational Therapeutics Core of the Cleveland Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center, Barchas’ gift will provide resources for initial exploration of the kinds of breakthrough ideas federal agencies and other large organizations are hesitant to back without significant evidence of their promise.

“Thanks to Dr. Barchas’ vision for advancing the treatment of patients with mental illness, our laboratory will be able to pursue creative and innovative approaches to discovering new therapeutic opportunities,” Pieper said. “These types of early stage, high risk, high reward strategies are not typically supported by traditional National Institutes of Health-style funding, and would be impossible without her philanthropic generosity.”